From April 24 to 25, 1995, an international symposium on research and the teaching of history in French-speaking Central Africa was held in Aix-en-Provence (southern France). This symposium was jointly organized by the Cameroonian universities of Yaoundé (of which Mveng was one of the founders of the history department) and the University of Buea. Strangely, Mveng, then the most important Cameroonian historian—if only for his impact within the department and his role in training young Cameroonians—was not invited.

From April 24 to 25, 1995, an international symposium on research and the teaching of history in French-speaking Central Africa was held in Aix-en-Provence (southern France). This symposium was jointly organized by the Cameroonian universities of Yaoundé (of which Mveng was one of the founders of the history department) and the University of Buea. Strangely, Mveng, then the most important Cameroonian historian—if only for his impact within the department and his role in training young Cameroonians—was not invited.

Even worse, two days before the symposium opened, on that tragic day of April 22, 1995, Mveng was brutally murdered. Yet, the organizers and participants made no official mention of his name or his tragic end, whether in the opening or closing speeches of the symposium or in the publication of its proceedings in 1997. Mveng had seemingly disappeared from the memory of those he had trained at the Federal University of Cameroon—unless these former students, who were also my own teachers, deemed the political implications of mentioning his name too burdensome.

Engelbert Mveng was born in Enam-Ngal, in southern Cameroon, on May 9, 1930, to Presbyterian parents but was baptized into the Roman Catholic faith in 1935. He attended Catholic school, first in Efok (1943-1944) and then at the Minor Seminary of Akono (1944-1949) in eastern central Cameroon. In 1951, he joined the Society of Jesus—then absent in Cameroon—at Djuma (Congo-Zaire). After two years in Djuma, his superiors sent him to Wépion, Belgium, to study philosophy (1954). Mveng studied in Belgium and France before returning to teach and conduct research on the art and history of his country. During Cameroon’s war of independence, he taught history as an intern at Collège Libermann in Douala (1958-1960). Having lived abroad for a long time, Mveng was eager to rediscover Cameroon’s hinterlands and its culture. He conducted extensive fieldwork among the Grassfields, Bamileke, and Bamun peoples, which led him to develop a keen interest in the immense wealth of Cameroonian art.

In the introduction to Cameroonian Art (Sept. 1963), his first publication in Abbia, Mveng positioned Cameroon’s history at the crossroads of world history. The article focused on art. However, Mveng also sought to demonstrate that the first contact between Cameroonians and the Atlantic world occurred in the sixth century BC, not during the fifteenth-century maritime revolution. At that time, the Carthaginian Hanno, the expedition of the Egyptian Necho, and the Greek explorers Scylax of Caryanda, Heraclitus of Pontus, and Eudoxus of Cyzicus are believed to have approached Mount Cameroon, which Hanno named “Chariot of the Gods” (“Cameroonian Art,” p. 4).

The articles in the journal Abbia did not include footnotes. Mveng’s article, therefore, does not cite his sources. To uncover them, one must refer to his doctoral theses. The first, Paganism and Christianity in the Letters of Saint Augustine (University of Lyon, 1964), was followed in 1970 by his State Thesis: The Greek Sources of Negro-African History from Homer to Strabo. In this work, interpreted here by Ntima Nkanza, Mveng argued: “Europeans denied Africans a place in history due to the absence of written sources. They would have been surprised had they taken their own earliest sources seriously. Africa is very much alive in Greek sources.” This became the central argument of Mveng’s entire intellectual work, whose primary goal was the rehabilitation of Africa.

His most well-known historical publication is The History of Cameroon. Mveng’s sources included extensive genealogical records and archives from Cameroon, Nigeria, Senegal, Belgium, France, and Germany, as well as oral traditions. He translated some of his sources from German into French and incorporated interdisciplinary methods, using ethnographic, missiological, geographical, and archaeological data. Mveng was convinced that authentic African studies epistemology must begin with anthropology—that is, “the human being as both subject and research subject”: “the human being as both subject and object of creative thought.”

Written in a classroom while he taught at Libermann, The History of Cameroon targeted both university scholars and students, as well as teachers and high school students seeking national identity in a newly independent Cameroon. Mveng was a patriotic historian. In this spirit, he co-authored the Cameroon History Manual (Yaoundé: CEPER, 1969) with Beling-Nkoumba. During the 1995 Aix-en-Provence conference, Professor Léon Taptué of the University of Yaoundé I stated that this book was the only reference available for history teachers in Cameroonian primary and secondary schools. Since all teachers and students learned their history from Mveng’s works, his books shaped generations of Cameroonians.

This influence, along with the theological and poetic turn in his later works, did not please everyone, particularly Elridge Mohamadou, whose intellectual impact would eventually be linked to Mveng’s legacy. In 1965, Mohamadou published a review of The History of Cameroon in Abbia, marking his first work as a self-made historian. He acknowledged that The History of Cameroon was the first serious book by a Cameroonian. Despite its 24 pages of bibliography and rigorous scholarship, Mohamadou criticized Mveng for focusing more on the Bantu and Christianized regions of Cameroon while “neglecting” the Pygmies and Sudanese groups in the central and northern parts of the country.

Mohamadou’s critique was exaggerated. Of the 189 pages devoted to pre-colonial Cameroon (pp. 71-260), 45 discussed northern societies, 8 covered the Bamun, 13 were on the Bantu, 20 on coastal peoples, and 11 on the Bamileke. The remaining pages addressed German-Duala treaties and their consequences.

Aware of these criticisms, Mveng never responded directly to Mohamadou’s review. However, in the preface to the second edition (1984), he acknowledged incorporating “advances in knowledge about Cameroon” since 1963 and made some revisions. Interestingly, Mohamadou’s Catalogue of German Colonial Archives in Cameroon (1978) and The Fulani Kingdoms of Adamawa (1978) were included in the bibliography.

At the beginning of his intellectual career, in addition to writing history, Mveng organized the First Festival of Black Art (1966) in Dakar, whose report was published in Abbia. As rapporteur for the 1965 International Congress of African Historians in Dar-es-Salaam, he defined the ultimate goal of African historiography in terms still relevant today, 30 years after his death: “The study of African history presupposes that African peoples are masters of their history: it is up to them to say who they were, who they are, and who they want to be! The duty of the African historian is to affirm this authenticity, independent of how foreign observers have depicted it.” This task remains an open field, its quest a great challenge.

What’s more, at a time when Cameroon’s identity and unity are under attack, Mveng’s silence in the face of Mohamadou’s acerbic (and rather unfair) criticism invites us to listen to the other as other, beyond the inappropriateness of his words. It’s much more a question of appreciating and recognizing the contribution of this other to the debate for the common good. It’s this recognition that Mveng subtly makes in the second edition of his Histoire du Cameroun, acknowledging the work of the man who, according to the review, could have been the object of his anger. This same edition of L’histoire du Cameroun has this astonishing conclusion, the last sentence even, challenging for Cameroon and Africa:

“If there’s one land where the tribes of this tribal Africa are destined to live without borders, without discrimination and without hatred, it’s our land. This is why violence is ‘unnatural’ here more than anywhere else. And no doubt, if the peoples of the world flock to the cradle of this newborn Cameroon, it’s because they’ve come to look to us for the example of a multiple, united world. This preface to the history of Cameroon could only end with words of peace, since this is the motto of our country: ‘Peace, Work, Country,’ we say to it with the Christmas angels: Peace on this earth and on its men of good will. END,” Mveng, Histoire du Cameroun (1984), p. 500.

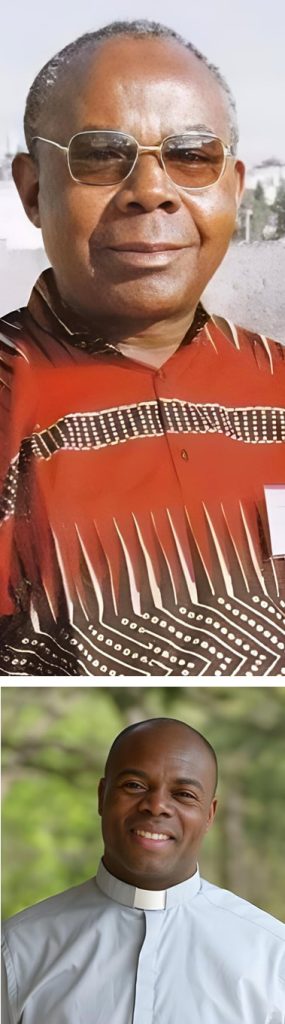

Jean Luc Enyegue, SJ

Director of the Jesuit Historical Institute in Africa